Over the last 200 years, the country has seen many trades expand and collapse, empires built and lost, an industrial revolution, slavery abolished, and wars won at a terrible price. Egham and its environs provide a local lens through which to view these changes in time and perspectives we have of the world. In 1822, when John Hassell painted many of his watercolours of Egham-based buildings, Egham was in the countryside. It was home to farmers, skilled labourers, tradesmen, as well as merchants, politicians, families of wealth and high-ranking military officials.

Hassell’s paintings record a snapshot of the architecture around Egham but show very little of the landscape in which they were set. This landscape, like the rest of the country underwent much change through the 18th and early 19th century and the stories of the buildings Hassell records are closely entwined with this transformation.

Although Surrey today is densely populated and land value is among the highest in the country, reports from travellers in the west of Surrey in the eighteenth century speak with one voice of a country of wild, barren heaths, ugly and useless for any agricultural purpose and therefore of very low value. As Daniel Defoe puts it in 1724, ‘a foil to the beauty of the rest of England, or a mark of just resentment showed by Heaven upon the Englishman’s pride’ (cited Crosby p.173). About a century later the plain speaking Cobbett writes ‘On leaving Oakingham for London, you get upon what is called Windsor Forest; that is to say, upon as bleak, as barren, and as villainous a heath as ever man set his eyes on. […From Sunning Hill] you go across a corner of Windsor Park, and come out at Virginia Water. To Egham is then about two miles. A much more ugly country than that between Egham and Kensington would with great difficulty be found in England. Flat as a pancake, and, until you come to Hammersmith, the soil is a nasty stony dirt upon a bed of gravel.’ (Cobbett, pp.66-68).

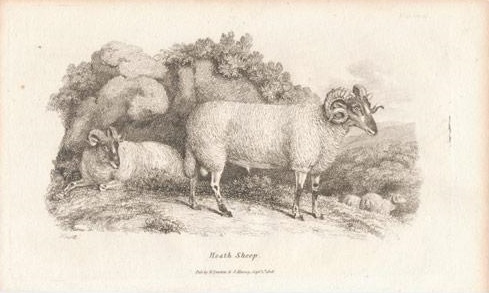

Image Credit: Engraved by Samuel Howitt and published by Darton and Harvey

Although there was some fertile land near the Thames, the heathland had predominantly thin, sandy soil punctuated by places where clay created waterlogged areas and peat bogs. The heaths were useless for arable or other crop farming and sparsely populated. The only livestock seen in this landscape would have been a few cows, owned for milk, and a breed of small scraggy sheep which, in this great age of ‘improvement’ and animal breeding, were also remarked upon disparagingly: ‘a pure heath sheep is a remarkably ugly creature, with very large horns, and seldom weighs more than eight pounds per quarter.’ (Thomas Allen 1829, cited Crosby p.174). In addition, it was widely accepted that this unfortunate landscape had an unhealthy effect on the mental state of its inhabitants. In 1840 Brayley records an old saying that the inhabitants of the western borders of the county ‘only knew when it rained by looking into the ponds on their heaths and commons’ (Brayley Topographical History of Surrey, I p.437 cited Crosby p.178)

Contemporary writers took little notice of and placed little value on the activities of cottagers and small tenant farmers who used the common and heathland. They would have farmed what useful land there was communally producing some corn, and root crops, probably broadcast sowing rather than sowing in drills which was more efficient and suitable for ploughing out weeds etc. The heaths held essential resources for the poor who would have dug gravel to improve roads, grazed cattle or the heath sheep described, gathered material for thatch, firewood and kindling and dug turf for fuel. In 1813 local women were recorded in the Bagshot and Windlesham area cutting heather to make besom brooms and gathering whortleberries for sale although the author refers to these activities dismissively as ‘miserable productions and trifling employment’ (Stevenson 1813, cited Crosby p.175).

Researched and Authored by Katharine Stimston

References

BBC In Our Time programme on Enclosure: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00b1m9b

Cobbett, W. (1830) Rural Rides. Penguin English Library ed. G. Woodcock, 1967.

Crosby, A. G. (2018) ‘A disappearing landscape: the heathlands of the Berkshire, Hampshire and Surrey borders’. Agricultural History Review, 66:2 pp.171-98.

Parton, A. G. (1985) ‘Parliamentary enclosure in nineteenth-century Surrey – some perspectives on the evaluation of land potential’. Agricultural History Review, 33:1, pp.51-58.

Turner, Frederick. Egham, Surrey: A history of the Parish under Church and Crown, 1926

Further Reading

Bryan, T. A. The Egham Inclosure Act 1814 and the award. [Typewritten thesis with plan ]. 1947. [138], The Oliver Collection

Roberts, J. Royal Landscape: Gardens and Parks of Windsor. Yale University Press, 1997.

Waits, I. Common Land in English Painting 1700-1850. Boydell Press, 2012.

The Act to enclose land at Egham 1814 (Surrey History Centre, ref: 2225/10/1), and the resulting Award and Map 1817 (SHC, ref: QS6/4/25). Material related to this enclosure includes a book of reference to old enclosures and allotments (SHC, ref: 185/16/2) and related papers 1817 (SHC, ref: 373/-).

Microfilm of a written survey of Egham 1818 giving plots, owners, names of fields etc. old and new enclosures, Surrey History Centre, Z/246/1

Enclosure Maps at Egham Museum. Plus earlier 1805 map.

Edgell Wyatt papers – include discussion of land enclosed and the intention of some profit to go to poor relief.