At the time Hassell’s paintings were made, concepts of ‘poverty’ and being ‘poor’ lay at the knotty intersection of Christian morality, economic principles and theories of population. Historically, it was acknowledged that the poor were simply part of the social order and poverty should be greeted with charity, however in the period around the turn of the nineteenth century this certainty began to falter. The combination of the return of soldiers from the wars with France and sudden social and economic change at home that left many agricultural labourers without work and sometimes without homes, increased the number needing support. It created intense pressure on the systems which had hitherto provided relief for the poor. Poor rates in England and Wales rose from £1,720,316 in 1776 to a peak of £8,411,893 in 1820-1 (Lloyd, p.117) and across these years the population of England doubled.

At the end of the 18th century critics of economic reform, like William Cobbett, blamed social climbing farmers for pushing up prices and reducing rural employment, accusing them of spending on consumer luxuries rather than agricultural wages thus rendering agricultural labourers unable to live on what they earnt. The image of the vulgar and frivolous farmer’s wife with her tea service and her fashionable furniture was common [see Cobbett]. At the same time criticism of philanthropy began to emerge as people felt that the existing schemes for employing the poor neither educated and improved them nor created any profit. Worries about shortages of food and financial crisis drove these ways of thinking. Caring for the poor, traditionally influenced at least in some part by a sense of pity and morality, came also to be shaped by financial concerns and fear of unrest in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Poverty began to be understood not simply as part of the natural order of things but rather an unnatural and potentially dangerous state of dependence.

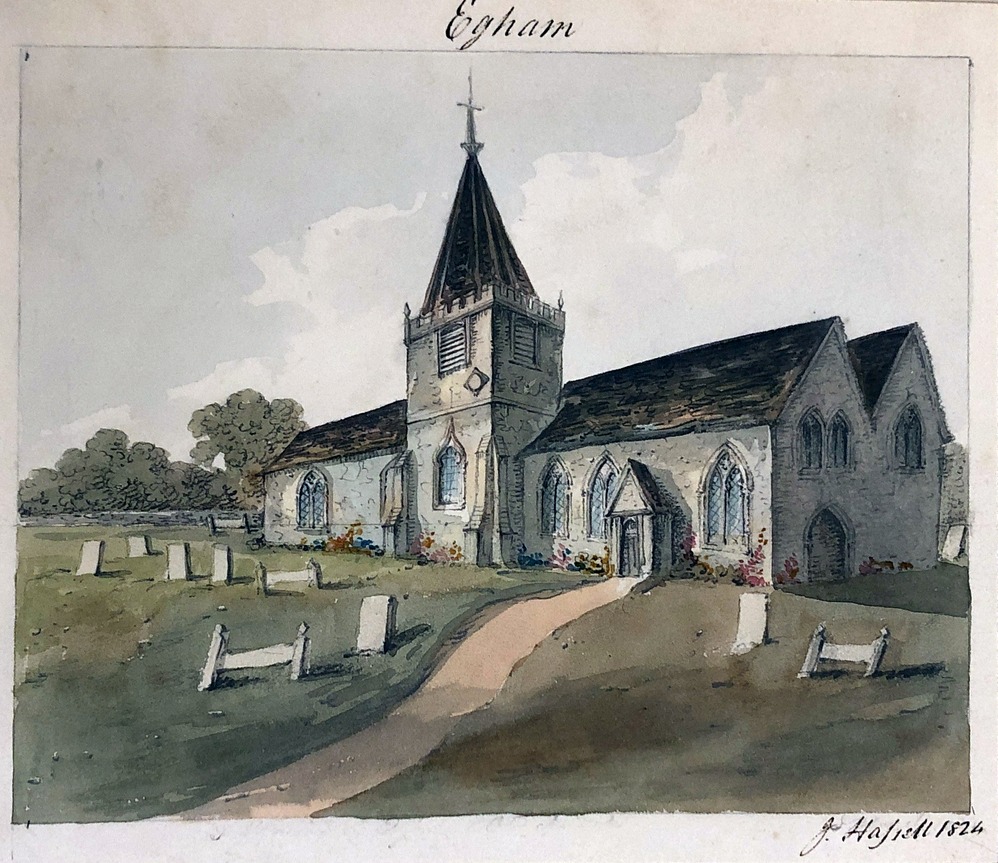

The Egham ‘House of Industry and Poor House’ and the ‘Work House’ in Hassell’s paintings

The Vestry Minute book for the parish of Egham for 1817-1824 (SHC 2516/6/2) and 1831-35 (SHC 2516/2/10) paint a picture of a parish responding to an increase in poverty and a strain on the systems in place to deal with it. Hassell’s paintings of the House of Industry and the new Work House tell this story.

The Vestry minutes list those whose issues have been addressed at the meetings, usually families asking for assistance with children’s clothes or shoes, wives who need extra money while their husbands are ill or other individuals who are unable to support themselves, some of which were sent to the poor house. Other issues relating to care for the poor were also raised at these meetings, such as the payment of doctors and disputes over grazing of animals and collecting of turf or kindling on the common waste areas. The period between 1817 and 1824 sees an increase in requests for help from people from outside the parish and reports of problems with beggars and vagrants.

A 1777 Parliamentary Report on provision for the poor lists Egham’s workhouse and states that it provided for 36 people, so it was a very small institution compared to those in big cities which could hold up to 700. This is most likely the residential part of the building in Hassell’s 1822 picture. An 1805 map (Museum ref: J.H03) indicates the workhouse (the term poorhouse and workhouse are used more or less interchangeably for residential institutions for the poor at this time) along with two cottages and gardens, on a plot on the Avenue.

Through 1817 and early 1818 these requests for help are listed and usually granted, occasionally money is given with no purpose noted which suggests a certain level of familiarity and trust between the parish overseers and the local poor. However, by 1819 Egham was undoubtedly experiencing an increase in poverty very likely as the result of the labourers forced off the land by the local enclosures of the first two decades of the century. The non-specific giving of money disappears, more requests are refused, more people are sent to the poor house and the minutes demonstrate a sense of an increase in demand for assistance and a strain on the administrative systems that provide that assistance. Several householders are chased for late payment of their poor rates and people who are working but still receiving help are told to give up either the help or their wages. For example, John Hawkes who, on the 2nd May 1819, was instructed ‘to take his family out of the Poor House or to pay his earnings to Mr Duck’. At this time there are also reports of ‘unpleasant annoyance by beggars infesting the parish’. In response to this it was resolved ‘two proper persons be appointed as Beedles or special Constables, in order to clear the parish of the same, and further the two persons so appointed be provided with proper staffs, great coats, and hatts’. Parish provision for the poor was evidently feeling the strain by 1820.

The great majority of requests to the Vestry are for assistance for children. On the 4th of January 1819 a meeting was held to consider ‘the means of employing the children of the parish now supported by the parish rates in works of industry. It was unanimously resolved to form an establishment for the purpose’. The costs of this was estimated at £54 15s with the money to be supplied by Mr Wetton from a sum that had been subscribed to aid the poor. By May it is recorded that a Robert Garnsey would be employed at £1 4s a week to teach the children, the Vestry minutes recording that ‘all persons who receive alms of this parish for the support of their respective familys are hereby directed to send the same to the House of Industry (so provided) in order they may be taught to spin knit etc., further that all other persons who are receiving alms for their [own] support are also ordered to attend the same or shew cause why they do not’. People who did not comply would have their weekly poor allowance stopped unless their absence could be justified.

The term ‘House of Industry’ was commonly used in the late eighteenth century to denote a non-residential institution where the poor, especially children, were put to work. This was a cheaper way of dealing with poverty and meant that families could still live together at home. Sometimes the wages of the working members of the household would also be subsidised based on the size of the family or the price of bread. In the case of the institution that Hassell painted in 1822, it seems that the House of Industry was built on the same site as the existing poorhouse.

The tenants of the cottages mentioned on the map, William Brewin and Edward Goodman, could possibly have been supervisors at the House of Industry or poorhouse.

By 1823 there are many more requests for aid from people coming from outside the parish and a growing sense of pressure on limited resources and it is clear that the current poorhouse provision is inadequate. A Magistrates order of the 24th of January 1823 signed by local landowners and Justices of the Peace W. H. Freemantle, Thomas Rawdon Ward (whose houses are also recorded by Hassell – Elvills/Castlehill and Roundoak) reports that ‘the state of the workhouse is so bad as to be unfit and insufficient for the necessary support and maintenance of the poor persons who are kept there’. It is ordered that ‘some proper additions and repair be now made at the house as will make the place more comfortable, and that some further provisions, of fuel and bedding be immediately supplied, and that the Parish Officers do submit to the parish in Vestry assembled the necessity of taking some other house, or building a proper and sufficient workhouse’. Payment of Poor Rates had obviously become a problem too as there are also directions to regulate the system by which allowances are paid and to appoint someone to control this and all arrears are demanded under a threat of the issue of summons.

Life in the Poor House is obviously becoming uncomfortable, and overcrowded and it is unsurprising that this resulted at times in violence as reported on Sunday February 2nd 1823: ‘Mrs Copper, mistress of the Poor House, states that Stephen Portsmouth and Elizabeth Marks on Saturday February the first instant did cause a riot by fighting and swearing in the Poor House after their dinner on that day.’ They were given 21 days hard labour at Guildford.

So in January 1823, soon after the completion of Hassell’s painting, the Poor House is described as ‘in such a state of decay and dilapidation as to be unfit for the reception and lodging of the Paupers’. Plans are quickly made to build a new institution big enough to accommodate 50 persons for less than £800. Finding a plot of land proved difficult, but eventually it was requested that the small plot of land where the current poorhouse stood be acquired from the Office of Woods and Forests. Moses Duck, who was eventually appointed Assistant Overseer also become Governor of the Work House. The rent received from the building was put straight back into charitable causes.

The paint was probably still wet in the new workhouse when it was recorded by Hassell in 1824. The neat building in Hassell’s picture speaks of order and sufficiency but unfortunately the new building didn’t solve the growing problem for good. By the early 1830s, the strain on the parish resources and the increase in poverty among farm labourers in particular is obvious. The authors of a report dated 16th November 1832 are insistent that these people should be clearly differentiated from ‘paupers’ to avoid damage to their reputations:

‘In this manner the character of these Labourers would be kept up and they would be distinguished from the Paupers of the Parish; a consideration which it is extremely desirable to keep consistently in view, because although the wages should be kept down to induce these men to look out for work elsewhere, they should on no account be treated as paupers merely because they cannot find work, and are therefore employed by the Parish: If this system be carefully pursued, it will tend to prevent the idle from applying for parochial assistance, when they find that they must work hard for it, and will probably produce a tolerable return, applicable to the wants of the Poor House.’

Through 1833 the problem of late payment of poor rates is such that a committee is formed to address it. The job of Assistant Overseer is now deemed too labourious for one person to complete so another officer is appointed to assist Mr Duck in collecting the rates. By 6th January 1834 the ‘acceleration of the estimated expenses of the Poor’ combined with late rate payment resulted in the Parish being left in debt. The situation in Egham in the early 1830s was not unique. It would have been mirrored in parishes across the rural south of England and eventually resulted in the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. After 1834 Egham became part of the Windsor Poor Law Union and residential provision for the poor moved to the large Windsor Workhouse in Sheet Street. The new workhouse building was no longer needed and was put to other uses including a Police Station and, for a time, the Literary Institute.

Hassell’s paintings document a period of tremendous increase in poverty and the climax of a gradual but significant shift in the way the poor were viewed and treated in England. The 1822 image depicts the vernacular architecture of the old style poorhouse and the house of industry with its emphasis on supporting the poor in their own homes. The painting of 1824 shows an institutional building which came about as a result of huge pressure on the parish from increasing numbers of poor from both within and without its boundaries. The spirit of the New Poor Law can be felt in the transition between the two.

For more information, see Poverty and the Poor Law Timeline.

Researched and Authored by Katharine Stimston

References

The Companion to British History, ed. J. Gardiner and N. Wenborn, Collins and Brown, 1995.

Higginbotham, P. http://www.workhouses.org.uk/ (Accessed 20 July 2020)

Lloyd, S. ‘Poverty’ in An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age. British Culture 1776-1832. OUP, 1999, pp.114-125.

Surrey History Centre, Archive Sources:

SHC 2516/6/2: Vestry Minute book with plans for the new Work House. These records cover 1817-1824.

SHC 548/2/4/4 Rent Book c.1805-1844 with specific reference to Egham Work House (ff.43 and 63 and 164).

SHC 2516/2/10 Minute book for those overseeing the care of the poor 1831-35.